“Eat organic,” “eat better,” “consume responsibly”: these are all notions that revolve around sustainable food, but they are not enough to define it. What is really behind this concept?

For Marie-Béatrice Noble, environmentalist, ambassador for the European Climate Pact and member of Infogreen, “sustainable food means adopting a healthy diet by limiting animal products--meat, fish and dairy products--and ultra-processed foods, while favouring fruit, vegetables and pulses. But it also means paying attention to the waste generated by our eating habits, from plastic to food waste, while supporting local and fair trade and respecting animal welfare.” In short, it’s about eating food that benefits our health, our planet and future generations.

The former corporate lawyer and founder of MNKS (now PWC Legal) made a radical career change after watching the documentaries “Cowspiracy,” “Seaspiracy” and “What the Health.” “Changing our diet has a huge impact, because we make this choice at least 14 times a week, sometimes for the whole family,” she explains. “It also means changing the conversation with those around us, which takes a bit of courage, but we’re surprised by the collective goodwill and inspiring testimonials it generates.”

Adopting a sustainable diet remains a challenge. The and the . Noble remains convinced that “individual responsibility is the key to challenging the political and industrial sectors.” While a radical change in our eating habits is not always an option, moving towards a more responsible diet is essential for our health and that of future generations.

To eat more responsibly, there’s no need to radically change your diet or lifestyle. Here are three initiatives and tips to help you do just that.

Calculating your food footprint: a simple gesture

The question is no longer whether our food has an impact on the environment, but rather how. Online tools such as the allow you to calculate your personal food footprint.

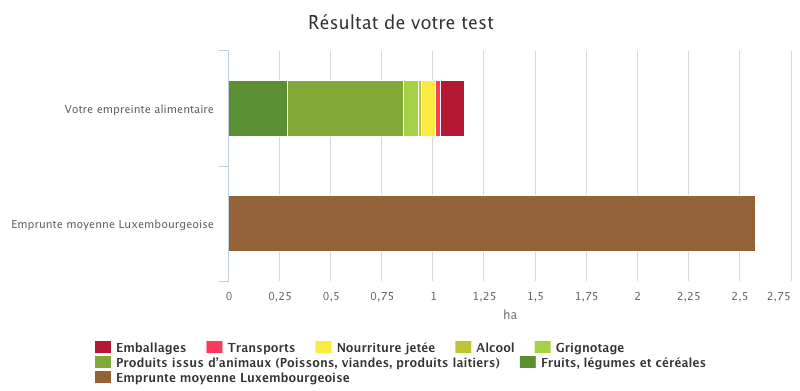

Expressed in hectares, the ecological footprint measures the pressure that our activities exert on nature, by evaluating the surface area required by a population to meet its resource consumption and waste absorption needs. Our food, along with housing, transport and goods and services, is one of the factors taken into account when calculating the ecological footprint.

While the ideal ecological footprint for a human being to satisfy all his needs is 1.78 hectares, the food footprint of Luxembourgers alone is already 2.58 hectares. To be exact, the food footprint of people in Luxembourg represents more than a quarter of their overall ecological footprint (9.41). In other words, if everyone on Earth adopted our eating habits, we would need more than one planet to meet our needs.

Let’s simulate the ecological footprint of what we consider to be a ‘normal’ consumer. This person eats fish from time to time (around 100g a week), dairy products and red meat once or twice a week, white meat four or five times a week and favours seasonal fruit and vegetables. He also has regular consumption habits: a few glasses of alcohol and snacks occasionally during the week, he sorts waste, avoids food waste, prefers European products and uses his car once a week to do his shopping.

Most of our food footprint comes from animal proteins. Changeons de Menu/Maison Moderne simulation

The result? His food footprint is 1.15 hectares, more than half the national average. Although this figure is still higher than the ecological ideals, this simulation shows that it is possible to reconcile well-being and environmental responsibility without giving up your habits.

The site offers practical advice on how to adopt a more responsible diet, and also provides a map of local retailers who favour quality, environmentally-friendly products.

Sorting out the real from the fake with applications

Adopting a sustainable diet remains a challenge, however. Food manufacturers blur the lines between healthy and harmful products. While it’s possible to eat everything in moderation, it’s best to avoid ultra-processed products, which are harmful to both our health and the planet.

Packed with additives, fats, salt and sugar, these products are designed to be both cheap and addictive, which explains their success. Their excessive consumption is directly responsible for the (1 in 8 people worldwide). Industrial breads, soft drinks, ready-made meals... are all everyday products that take us further away from a balanced diet.

Scientists are warning of the dangers of the ‘cocktail effect’ of additives, which can have dramatic consequences for our physical and mental health. Faced with this food jungle, how can we find our way around? One simple solution: avoid products with long lists of ingredients that are difficult to understand.

Applications such as Yuka have become veritable allies for health-conscious consumers. In just a few seconds, they analyse the composition of products and help us make the right choices. Founded in 2017, it has met with real success in our French neighbours and now has more than 40m users, according to CEO and co-founder Julie Chapon.

. Even if some experts criticise a lack of scientific rigour, the application remains an excellent way for neophytes to find out what they are consuming.

Yuka is a mobile application that analyses the composition of food and cosmetic products by scanning their barcodes. It gives a score and detailed information on their impact on health and the environment, Photo: Maëlle Hamma/ Maison Moderne

For example, orange juice is often seen as an excellent way of incorporating fruit and vitamins into our diet. However, a scan of the barcode on some brands reveals that they contain up to 10.5g of sugar per 100ml, the equivalent of a Coke.

, such as Buy or Not, which, by scanning the product, reveals whether or not the company selling it is ethical according to environmental criteria.

A flagship initiative: towards sustainable canteens

Young people are particularly affected by sustainable food issues. According to the UN, their eating habits are becoming increasingly unhealthy. One in four teenagers say they eat sweets or chocolate every day. On the other hand, only two out of five teenagers--38% to be exact--include fruit or vegetables in their daily diet. Among the reasons given, lack of time, knowledge and budget stand out as major obstacles.

With this in mind, the Luxembourg government, in collaboration with Restopolis, has launched the ambitious 2021 initiative “Food4Future: Towards more sustainable food systems.” The programme--which --is based on six objectives (the RestoGoals), aimed at making school and university canteens more sustainable:

- RestoGoal 1: implementation of the PAN-Bio 2025 action plan, to increase the use of organic products;

- RestoGoal 2: extending the range of vegetarian and vegan meals on offer, while encouraging sensible meat consumption;

- RestoGoal 3: giving priority to short distribution channels, with 70% of products coming from local producers;

- RestoGoal 4: reducing waste in production and distribution;

- RestoGoal 5: combating food waste;

- RestoGoal 6: raising awareness and educating the public about sustainable food.

To complement these commitments, Restopolis in 2023 launched a digital platform, Supply4Future (S4F), which enables producers and suppliers to offer their products to canteens. This system focuses on organic and local products.

As a reminder, this network comprises 112 restaurants and cafeterias in Luxembourg, serving around 70,000 diners aged between 3 and 70, in almost all the public secondary schools, the University of Luxembourg, the skills centres, the grand ducal police school and the state-run Eis Schoul basic school.

“By giving priority to local products, and in particular organic products, we are strengthening our Luxembourg agriculture, both in terms of diversifying its products and making the transition to sustainable production. We are promoting the health and conscious consumption of our pupils and teachers,” said education minister (DP) on 7 October.

Luxembourg is full of initiatives that support more sustainable and responsible consumption, beyond Restopolis. , for example, is an online shop offering local, organic and packaging-free products. , a social player committed to vocational integration, trains and employs people in the horticulture and local food sectors. Organic brands such as, and are also part of this approach.

Find out more about the Alimenterre Festival or on the .

This article was originally published in .