Are drivers on passenger or goods transport platforms sufficiently protected against attempts by these same platforms to “make the most of them?” That’s a question asked by LSAP MPs and , as well as the OGBL and the LCGB unions. , which showed both the numerous lobbying actions taken with the authorities and the pressure exerted on drivers.

“Less than two months after Uber announced its partnership with Webtaxi, . Like Uber, Bolt is known for its practices of social dumping and bogus self-employment”, the OGBL said in a statement. “Bolt claims that it is already in contact with drivers and certainly has no intention of setting up operations in compliance with Luxembourg labour law and the collective agreement for the taxi sector. This announcement is certainly also the result of the arrival of Uber, which was openly celebrated by the liberal-conservative government and the minister for mobility.”

Are the self-employed too dependent?

“While the drivers who work for the Uber platform are all employees of the Luxembourg partner, it would appear that according to the business model envisaged by Bolt, their drivers would all be self-employed,” adds the LCGB. “This is all the more worrying given that the platform charges them lower commissions than the competition. So this aggressive pricing practice could be detrimental to the existence of these drivers.”

In a parliamentary response, labour minister (CSV) provided some clarifications, which will have to be looked at in the light of the new European directive on platform workers. “The directive should ensure a balance between the protection of people who work on digital platforms and who find themselves in a vulnerable situation, and the development of new business models that take advantage of the opportunities offered by digitisation,” he said on 12 March when an agreement was reached in Europe, against the advice of France and Germany.

Read also

“Digital platforms of this type established in Luxembourg must have an authorisation for establishment in due form corresponding to their service offering. The type of authorisation required is to be considered on a case-by-case basis depending on a company’s activities, bearing in mind that a company may also have several different activities that are subject to an establishment authorisation.”

Uber Eats, mentioned in the parliamentary question, operates in Luxembourg from its Dutch entity and is therefore not “established in Luxembourg,” nor is Uber, which relies on its Luxembourg partner, Voyages Emile Weber, or even Bolt, whose head office is in Paris and which is expected to use professional taxi drivers who are themselves already subject to all the necessary registrations.

Legislation to come

The minister also asserted that “the government is opposed to the creation of a third intermediary status likely to create greater insecurity for people carrying out work via a digital platform. These people can therefore only have employee status or self-employed status,” the difference coming from the subordination contract between the platform and the delivery driver. “To assess whether there is a subordinate relationship in a case where they have to classify a contractual relationship, judges rely on a body of evidence to form their opinion,” Mischo added.

And then we get into the ‘subtlety’ of the case law. In addition to the concept of permanent establishment--very familiar in tax and financial market contexts, the famous “letterboxes” have always been a Luxembourg speciality--the minister limits the provision of services to “an absence of stable and continuous participation in the economy of the host member state,” which suggests that those who have no structure or partners will one day have to move on to another organisation. Except, he adds, that this stable and continuous participation is assessed on a case-by-case basis, again in accordance with the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union cited in his reply.

The European directive, which the Luxembourg legislator will have to ‘improve’--to the benefit of the worker, of course--provides for a presumption of an employment contract, which the platform will have to challenge in the light of the way in which the relationship between the platform and the driver-deliverer is conducted.

At the end of the year, MoveEU, an organisation of players including Uber and Bolt, complained that two out of five criteria were sufficient to requalify the relationship between them and a delivery driver. The five conditions were: to cap the amount of money workers can receive; to supervise their performance, including by electronic means; to control the distribution or allocation of tasks; to control working conditions and impose restrictions on the choice of working hours; to impose restrictions on workers’ freedom to organise their work; and to impose rules on workers’ appearance or conduct.

It is not uninteresting to look at the other two market players mentioned in the question: they do not interpret the law in the same way. WeDely has two licences, one for “commercial activities and services” and the other for “transport of goods by road,” while Goosty only has one for “commercial activities and services.”

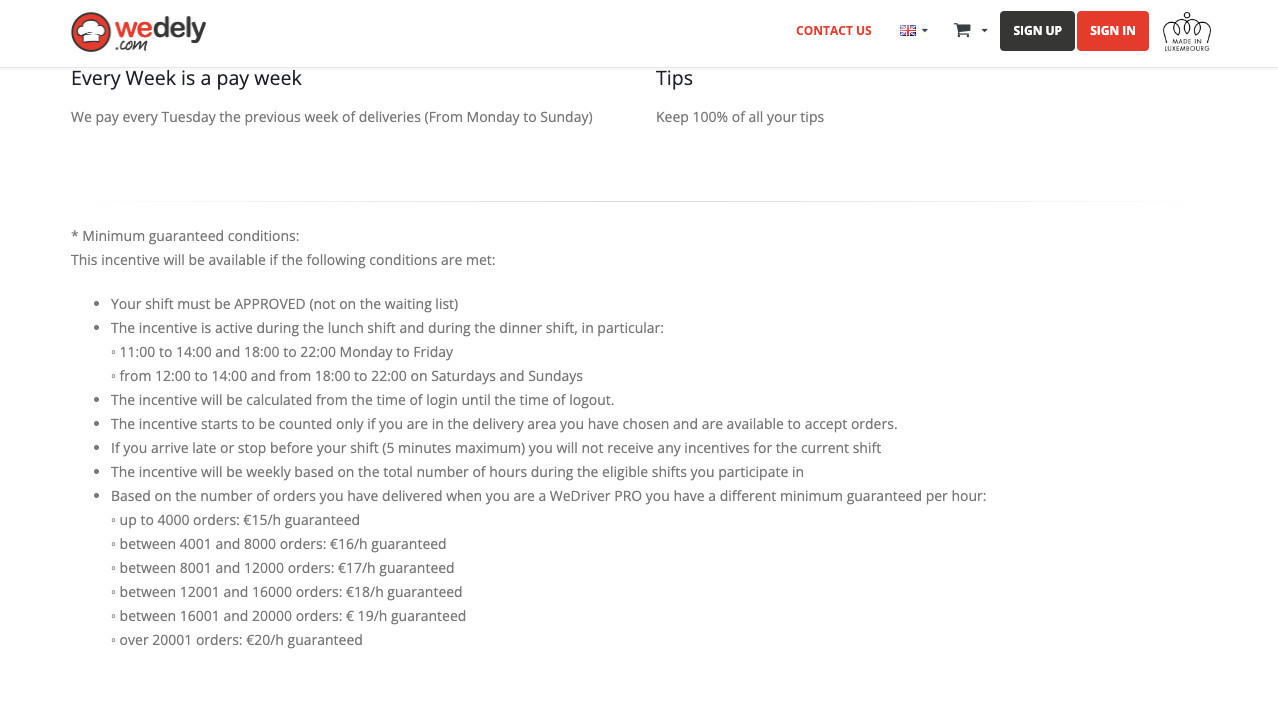

The conditions that a delivery driver must meet in order to be the best paid. Source: WeDely website

In its online section, the delivery applicant for Goosty must be self-employed or registered as a business. For WeDely, the applicant must have an authorisation to set up in accordance with the list of necessary documents and promises up to €20 per hour provided that the delivery driver meets a certain number of conditions (number of deliveries, availability during different peak times depending on weekdays and weekends).

This article was first published in French on . It has been translated and edited for Delano.