This little leather perfecto motorcycle jacket from a major Italian fashion house in a limited edition that you can’t find anywhere else. Or that pair of shoes from the famous brand with the red sole-- on sale for half the original price. Then there are those dresses from premium brands--or even top-of-the-range brands--sold for almost the same price as a fast-fashion dress. Or that bag from a leading French fashion house that a young working woman will--at last--be able to afford. Secondhand pieces, sometimes rare, but always sold for less than in the shop: that’s the credo of secondhand.

And it’s a market that is now worth more than €1.28bn worldwide and has already won over 87% of Europeans, driven by a fall in purchasing power, the explosion of e-commerce and growing ecological considerations on the part of consumers, reports Wavestone, a strategy and management consultancy.

In Luxembourg, there are now around ten shops of this type in the capital alone, with a variety of positioning. Among them is Second Hand Shop Lena, located on Avenue de la Faïencerie in Limpertsberg, one of the oldest in the country. It is run by Thi Thu Ha NGuyen, a dressmaker by trade with a passion for fashion. She took over the shop in 2008, “but it had already existed for 16 years before I arrived,” she explains. On two floors, there are luxury and high-end pieces for women, men and teenagers.

The owner opted for the depot-sale formula, like the majority of Luxembourg shops of this type. “It avoids the need to buy stock and means we can offer new products more often, depending on the season,” she explains. But the formula also has its drawbacks. “It involves a lot of work, you have to write everything down, keep a record of everything, know which piece belongs to which customer. It requires a lot of organisation.” Although, unlike others, she manages to close her accounts with a positive net result, “there’s no magic formula,” she says. “If you’re open, you enjoy what you do, you talk to customers and offer advice, I think the turnover takes care of itself.”

We analysed the annual accounts of six businesses of this type--published in the commercial register--and found that only two managed to make a profit at the end of their last financial year. The other four showed deficits of up to ten thousand euros. Even so, we can see that they have gradually managed to turn things around in recent years.

An increasingly unprofitable business

On Rue du Fort Neipperg in the Gare district, Michel Lindner, the owner of the Trouvailles shop that opened in 2018, talks about a business that is becoming less and less profitable. “It’s become more difficult in recent years, firstly because there are more and more boutiques and pop-ups. Since covid, everyone has gotten involved. Customers are attracted by novelty and like to change, to see what’s on offer elsewhere. Add to that inflation and the war in Ukraine, and people are buying only what they really need,” he says. He now works with just one sales assistant, rather than two.

Located on Rue du Fort Neipperg, Trouvailles is coping with declining profitability due to increasing competition, inflation and cautious customers, by focusing on buy-resale of affordable brands rather than depot-sale. Photo: Maëlle Hamma/Maison Moderne

In contrast to his competitors, Lindner has abandoned the depot-sale formula, which he considers too restrictive, and instead favours purchase-resale. This means mobilising cash to stock the shelves with secondhand items, mostly from mainstream or premium brands. “Here, we’re in an area where customers are looking for ‘cheap,’” he points out.

A question of price?

But how much does the price argument weigh in the growing secondhand trend? In Luxembourg, the last comprehensive study on the subject dates back to 2021. Carried out by the grand duchy’s market research and polling organisation Ilres, it showed that clothes, shoes and fashion accessories are the types of product most concerned by reuse: 61% compared with 31% for furniture and 24% for household appliances. One-third of adults (34%) said they had already bought secondhand clothes and 27% who had never done so said they were ready to do so.

The study in question also looked at the reasons that lead to this type of purchase: we find in fact the price argument (46%), ecological motivations (29%) or the desire of consumers to fight against overconsumption and waste (19%).

More recently, in 2023, the EU’s statistics bureau Eurostat consolidated data on people who cannot afford to buy new clothes in Europe. In Luxembourg, only 3.6% of the population is in this situation, much lower than in neighbouring countries (7.3% in Belgium, 9.4% in France, 7% in Germany).

An increasingly consistent offer

Also in 2023, the Chamber of Commerce’s Retail Report reported a significant increase in alternative sales formats in Luxembourg, with secondhand fashion stores in particular up 42.9%.

Located on Boulevard Royal, the Royal Second Hand boutique is seeing a decline in ostentatious luxury in favour of more discreet pieces, adapting to a varied clientele by focusing on an accessible selection and a depot-sale model that has been strengthened by the economic climate. Photo: Maëlle Hamma/Maison Moderne

The secondhand shop owners we interviewed all spoke of a trend that surged after covid and increasingly fierce competition. At Royal Second Hand, located on Boulevard Royal and also one of the oldest in the country, Isabelle Boez and Lino Intini are also guided by their love of beautiful pieces. “After covid, there was a big boom in secondhand luxury goods. Today, however, this has faded and we’re seeing more of a trend towards discretion, with less luxurious, more discreet pieces [what’s call the ‘quiet luxury’ trend, editor’s note]. This can perhaps be explained by the growing insecurity in the city,” she believes. On the other hand, classics such as the Kelly or the Birkin by Hermès are still very much in demand.

To stay ahead of the game, Boez and Intini try to select pieces that suit all budgets, and their clientele includes tourists and locals alike. “More and more people are entrusting us with clothes on consignment, which can no doubt be explained by a need for money given the economic climate, but also because people have less of a need to hoard. For our part, we have to be able to choose the right pieces that will appeal to our customers, authenticate the luxury pieces, and set the right price, which is done through discussion,” explains Boez.

Committed to fighting fast-fashion, the Dress and Co boutique on Rue des Capucins offers a premium and vintage selection on consignment, excluding certain brands and focusing on a carefully curated offering. Photo: Maëlle Hamma/Maison Moderne

These “constraints” or difficulties don’t stop younger shopkeepers--who say they are guided by their ecological conscience--from taking the plunge. This is particularly true of Caroline, the owner of Pardon My Closet on Avenue Monterey, and Elias Adjaoud of Dress and Co on Rue des Capucins. Both initially experimented with the “pop-up” format before perpetuating their business in rented commercial premises.

“What drives me is the ecological aspect and the fight against fast-fashion and its excesses,” says Adjaoud, who has chosen to “ban” certain brands, such as H&M or Zara, from his shop and to develop a more “premium” offering with brands such as Sandro, Maje or Claudie Pierlot and a focus on the latest trends and original vintage pieces.

He too has opted for the depot-sale formula. “It involves coming to an agreement with the seller and we always manage to come to an agreement. To set prices, I also base myself on a sort of ‘argus’ that exists in our business,” he explains. Is it enough to make a living from it? Not always, according to the young entrepreneur. “We manage to pay the rent, which is something. Some months work better than others,” confides the man who has also made the choice to offer a few new pieces, rigorously selected.

Despite the growing number of shops, the boss of Pardon My Closet talks about offers that complement each other. “Some boutiques focus more on vintage pieces, others on luxury. Sometimes I refer people to other secondhand shops for specific pieces.” However, given the size of the country, “this small market could quickly become saturated,” Caroline believes.

The young woman wants to target a wider customer base with pieces for all types of budgets. “I’m more focused on style than on the brand. My bet is that you can be stylish with secondhand clothes. There’s also a notion of service, with a desire to change people’s perception of fashion, to give clothes a second life.” And this can be felt in the layout of the boutique, where the pieces are carefully thought out in terms of how they are displayed, by colour.

Whilst “passion” and “ecological awareness” seem to guide the youngest members of the team, they still have to be able to make a living from it... “We have a lot of expenses, particularly rent, which is rather high in Luxembourg. And our margins are inevitably lower than those of an ordinary shop. It’s clear that we won’t make millions, and life is getting more and more expensive. It’s also worth remembering that although we’re talking about secondhand clothes, we are subject to VAT,” she stresses.

Competition online

Not to mention that competition is now also being played out online. Even if “the customer experience is nothing like in a boutique where there is a human aspect, where you can touch the items, try them on... But we have, for example, customers who will come and try on a piece in the boutique and end up buying it online. That’s the game, and in a way, the two modes of shopping complement each other too,” says the head of Pardon My Closet.

Vinted, which has just published its results for 2024, , thanks in particular to the integration of new markets and the strengthening of its luxury and electronics businesses. A year after the launch of the Lithuanian company, founded in 2008, a similar platform was launched in France in 2009: Vestiaire Collective.

Vestiaire Collective is an online platform specialising in the sale and purchase of secondhand clothing, shoes and fashion accessories, mainly from high-end and luxury brands. Photo: Shutterstock

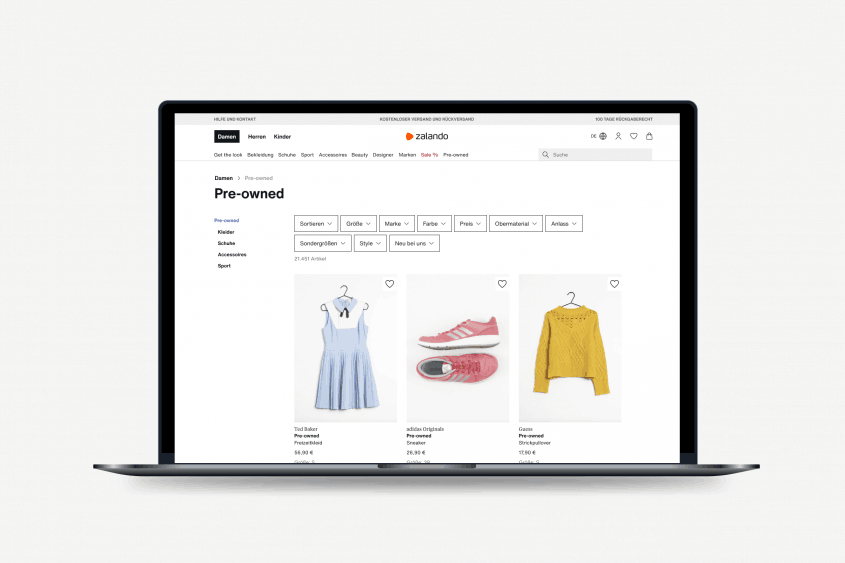

But more recently, some giants have also entered the fray, such as Zalando which, in addition to its new items, has been offering second-hand items in its “pre-owned” category since 2020, in 13 markets as well as in some of its outlet shops located in Germany. “By offering this category, we are bridging the gap between the excitement of shopping, novelty and self-expression, whilst encouraging a more conscious consumption of fashion items, with unparalleled simplicity,” explains a spokesperson for the brand, who refuses to give any figures on the number of items sold or users of this new offer. As an indication of the trend, however, “the most popular brands achieve 50% or more of items sold within 24 hours of going online. For premium brands, up to 90% of items are sold on the day they are launched.”

The solution devised by Zalando also allows customers to combine new and secondhand items in the same order. “The pre-owned business represents a significant market opportunity, as more and more customers are looking for quality items at reduced prices while adopting more sustainable fashion choices,” adds the online fashion platform’s representative, who asserts that since the launch of this offer, “interest in this category has continued to grow, with sustained demand over the last two years and sales speed doubling.” Zalando therefore intends to continue developing this “highly relevant” offer for its customers. Which could give other online fashion giants ideas...

Launched by Zalando in 2020, Zalando Pre-Owned is an initiative that allows customers to buy and sell secondhand clothing and accessories in excellent condition, from more than 3,000 brands, directly on the online platform. Photo: Zalando SE

Not to mention new concepts for “consuming” fashion in a different way, such as Le Closet, a French subscription-based clothing rental service launched in 2014 that allows women to renew their wardrobes in a flexible and eco-responsible way. The concept is based on sending out boxes containing clothes and accessories selected according to the subscriber’s preferences. They can wear these items for as long as they like. Once the items have been returned, a new box is sent out, allowing customers to continually update their wardrobe without having to make a purchase. This model aims to allow customers to vary their style without excessive accumulation of clothes, while still having access to quality pieces.

This article was originally published in .