When preparing for this discussion, Paperjam noted that guichet.lu defines the concept of wear and tear (usure normale, in French) as a hole on the wall to hang something. That, unfortunately, is not very helpful, as became evident during our interviews with Quentin Martin and Michel Nickels.

Avoid “tears for fears”: what are the rules on wear and tear and the end-of-life/life cycle of objects?

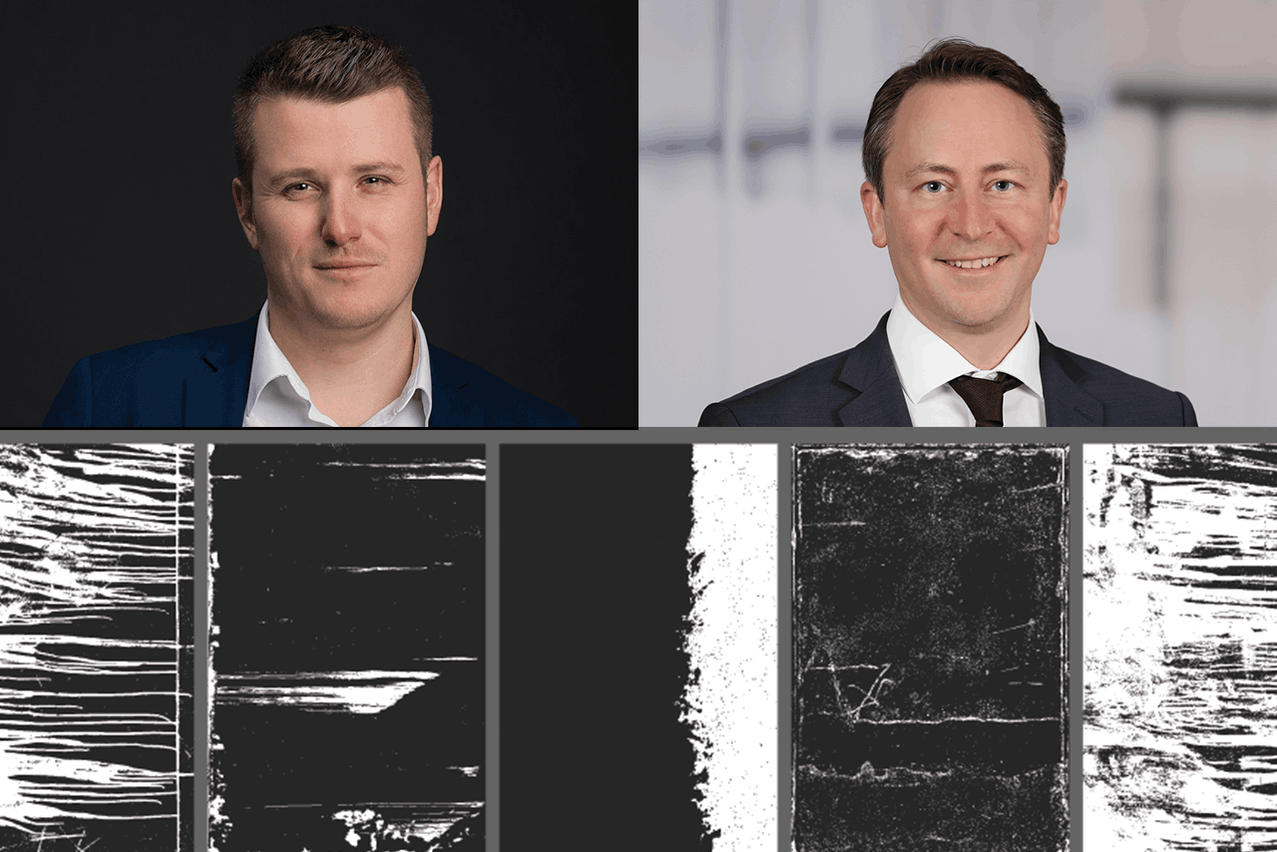

“It’s a mass litigation topic,” said , counsel at DSM Avocats à la Cour during an interview on 22 August 2024. “According to the Civil Code, when no check-in inventory was executed, the tenant is presumed having received the dwelling in good conditions and must return it as such unless they can prove they are not responsible for the degradation . However, when a check-in inventory was executed, the tenant must return the rented object as initially received except for degradation as per end-of-life/life cycle or force majeure. “

Martin suggested the best approach to address the concept of wear and tear and the end-of-life/life cycle, is to review the jurisprudence, a challenging undertaking for a person on the street who may not have the necessary legal knowledge.

To make the case even more complicated and frustrating for all parties, Martin commented that “it is a case of sovereign appreciation by the judge to determine if a damage is related to wear and tear and the end-of-life/life cycle, or not.” The judge will decide “whether suspected damage may have occurred under normal usage,” as per the document provided. The judge may use the jurisprudence, but the case in question will likely have different features.

Some examples: walls

Martin attempted to give some guidance. “Walls get yellow, wallpaper peels off and technical infrastructure weakens…. it is normal that those are not the responsibility of the tenant.” Martin and , partner at Elvinger Hoss Prussen, also commented that a judge would not see deep scratches on the wall in the same way as surface scratches. Nickels offered an example, saying, “A hole in the wall to hang a 100kg object is not the same as hanging a poster.” For those cases, a tenant should have requested an authorisation from the landlord, Nickels said during an interview on 27 August 2024.

On the other hand, humidity on a wall generated mainly by faulty behaviour of the tenant (poor ventilation of the premises, in particular) will not be considered as falling within the concept of normal wear and tear and the end-of-life/life cycle. If, on the other hand, the condition of the wall results from both faulty behaviour on the part of the tenant and a deterioration of the materials linked to the passage of time or normal use, “the judge may be required to order a sharing of responsibility. between the tenant and the landlord.”

Nickels explained that cases of moisture are challenging even for the court, as a bailiff or even a sworn expert may be called in to establish the cause (such as lack of airflow by the tenant or a faulty structure) to support the judge in his decision.

Gas boilers and floors

The annual maintenance of the gas boiler is to be charged to the tenant, whereas its replacement is a charge for the landlord (unless it breaks down because of a lack of maintenance). As the maintenance costs are to be paid by the tenant, it is likely that those fees are part of the annual statement. All large structural maintenance costs should be paid by the landlord.

Nickels noted several cases of disagreement regarding scratches on wooden floors, but didn’t see any other possibility besides involving a third party on persisting disagreements. Yet he insisted that a wooden floor will show scratches by simply walking on it. “It’s impossible not to have somehow worn it out.” However, he added: “a hole on the floor… or walking systematically on it with hard heels are another matter.”

Repainting or not

“The rules on the matter are not in the law but rather more in the case law,” specified Nickels. The first step is to check whether this is in the contract. “A clause in the contract specifying that the tenant must repaint after one, two or three years is valid.”

Martin reported that case law has demonstrated that rental contracts requiring a full repainting of the flat have been accepted by the courts. It’s considered as part of the normal maintenance cost.

When the clause is not in the contract, the judge is left to decide on the circumstances. Both lawyers said that “repainting is also subject to the rule of wear and tear and the end-of-life/life cycles.”

Dwellings get old even when they are unoccupied

Nickels noted that the law of July 2024 introduced the concept of wear and tear and end-of-life/life cycle (usure et vétusté normale) without defining it. He admitted that it is not possible to have these concepts defined as each case is different.

He commented that the concept of wear and tear and the end-of-life/life cycles does not apply anymore when a flat has been occupied for 30 years. “Everything has to be renovated… a judge will promptly reject a request by the landlord asking the tenant to repaint the walls.”

A window installed 20 years ago, for instance, has passed its normal life, said Nickels. A tenant would not be held responsible should they have the bad luck to break the handle when opening it. But a broken faucet that’s only two years old would likely fall under the responsibility of the tenant.

Importantly, Me Martin pointed out that the concept of end-of-life/life cycle was not expressly included in the old version of the law of September 21, 2006, but that it already appeared in the provisions of the Civil Code regarding rental leases.

Compensation for unavailability ( indemnité d’indisponibilité )

In the event of proven damage to the property, the tenant must not only pay for the repairs, but may also be required to compensate the landlord for the loss of use caused by the work in cases where the flat cannot be occupied. “Depending on the extent of the work, the former tenant may be liable for five or six months of rental losses,” warned Nickels.