An investigation this week revealed more than 50,000 potential targets of the Pegasus spyware commercialised by Israeli firm NSO. This included world leaders--such French president Emmanuel Macron and South Africa’s Cyril Ramaphosa--as well as opposition politicians, human rights activists and journalists.

“I had no idea that this thing is on my phone,” Panyi told Delano in an interview. The software exploits vulnerabilities in applications such as iMessage or WhatsApp to infiltrate the device, no longer requiring users to open a message or click on a malicious link.

While his initial reaction was to consider the attack as a “badge of honour”, Panyi’s feeling are mixed. “It’s a little humiliating to see my name on a list next to Hungarian criminals, mobsters, involved in murder and drug trafficking.”

Panyi was surveilled for six months in 2019. “It’s really scary,” he said. “Not only my work emails or my messages could have been accessed but also personal photos, personal videos. They could have turned on my camera or my microphone.” The analysis showed that between 50 to 100MB of data was exfiltrated from his device.

“My sense of privacy is destroyed. I cannot really feel secure. These are things that I have to deal with psychologically,” Panyi said. “This is such a violation of my very basic rights, not just my privacy rights but also my rights as a journalist to protect my sources. There should be no excuse for this.”

Protecting sources

Panyi works for investigative journalism not-for-profit Direct36 and has reported, among other stories, on shady government deals sealed with China and Russia under Viktor Orbán, corruption, rule of law violations and other national security and foreign policy topics.

“The worst part is that my sources could have been compromised,” he said. The journalist has begun relying less on technology, taking pen to paper, meeting with sources face-to-face in places away from the prying eyes of CCTV cameras.

“We have to go back to this very old-fashioned, analogue way of communicating, which will really slow down the work process, especially gathering information. But there’s no other way. We have to protect our sources and I really feel bad that even if I did everything, even if I was believing that I was protecting my sources, I was not. I feel terrible because of that.”

Hungary’s surveillance programme is only one chapter in a story that spans the globe, from the Mexican president’s inner circle to the entourage of the exiled Dalai Lama in India.

It’s no coincidence that Hungary is an ally of Israel in the EU, Panyi said about the scandal’s foreign policy dimension. Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates--also NSO clients according to the file--signed peace deals with Israel last year. “I believe this whole acquisition of Pegasus by these countries was linked to the previous Israeli administration.”

Dubbed Pegasus Project, the spyware investigation involved more than 80 reporters from 17 media organisations in ten countries, coordinated by Forbidden Stories, an organisation that provides secure communications channels to journalists, with support from Amnesty International.

Brussels inaction

Panyi found out he was one of the targets after being asked to forward his phone number to German investigative journalist Frederik Obermaier of the Süddeutsche Zeitung. “He asked us to establish a secure line of communications, because he wants to tell us about a very interesting project.” Panyi’s colleague, András Szabó, was also on the list.

A forensic analysis of Panyi’s phone by Amnesty International confirmed that it had been hacked. “I was a member of this team who was not only investigating the story but also part of the story.”

Hungary is the only EU member country cited in the revelations. “This is not the way I should be treated as a citizen of a European Union member state,” Panyi said. But he doesn’t expect much from Brussels: “Putting out statements but, as usual, no action.” The EU has failed over the past decade of the Orbán government to prevent a deteriorating of rule of law, democracy and press freedom, the journalist said. “I can’t imagine that this would be any different.”

The Orbán government claims the Pegasus revelations are part of an orchestrated smear campaign. But Panyi said there is no doubt that it perpetrated the attacks. Around 300 phone numbers from Hungary were included in the list and Panyi and his colleagues continue to work on identifying some of their owners.

Luxembourg complicit

The Luxembourg government this week confirmed that there are nine NSO entities active in the grand duchy.

“Tax havens in and outside of Europe, from the Netherlands to Luxembourg, are of course complicit because these companies are making tons of profit,” Panyi said. “When it comes to the role of those countries that are hosting the legal entities, they are also profiting from the profit that was made spying on journalists, political opponents, human rights defenders.”

Already in 2018, Luxembourg was linked to NSO Group when the Pegasus spyware was connected to the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. But the government said the subsidiaries in Luxembourg do not export cyber surveillance technology from the country and that it would not investigate the matter.

“Obviously, there is a role,” Panyi said of countries hosting the firm’s subsidiaries. “It’s a minor role, but every country should consider what kind of activities it tolerates to be registered on their soil.”

The case has sparked renewed calls for national due diligence legislation. During a press conference this week, Asselborn said that Luxembourg would act if NSO committed human rights violations from its offices in the grand duchy, but that the company’s presence here is limited to back-office activities.

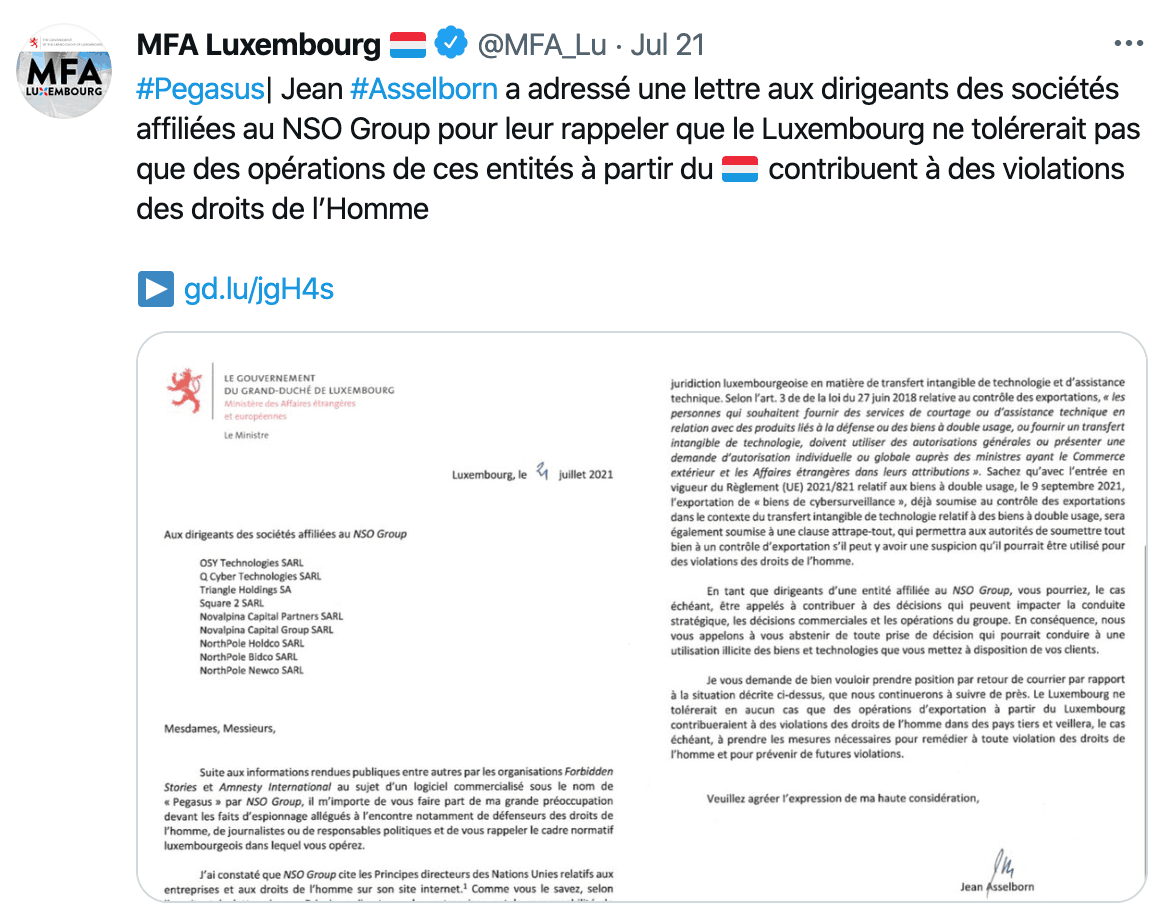

The foreign ministry sent a letter to the NSO entities in Luxembourg this week Photo: @MFA_lu via Twitter

Regulating the spyware industry would be a first step in curbing abuses like the ones uncovered by the Pegasus Project, Panyi said. “On a global scale, the spyware industry is unregulated. That should end.” Hackers, for example, identify systems’ vulnerabilities and sell this knowledge to spyware companies. Developers meanwhile are racing to plug the holes.

NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden in an interview with about the NSO spyware said it’s an industry that should not exist. “If you don’t do anything to stop the sale of this technology, it’s not just going to be 50,000 targets. It’s going to be 50 million targets, and it’s going to happen much more quickly than any of us expect,” he said.

NSO has denied wrongdoing, saying it sells the software only to vetted clients with the aim to fight crime or terrorism. The company this week it would no longer respond to media requests and “not play along with the vicious and slanderous campaign.”