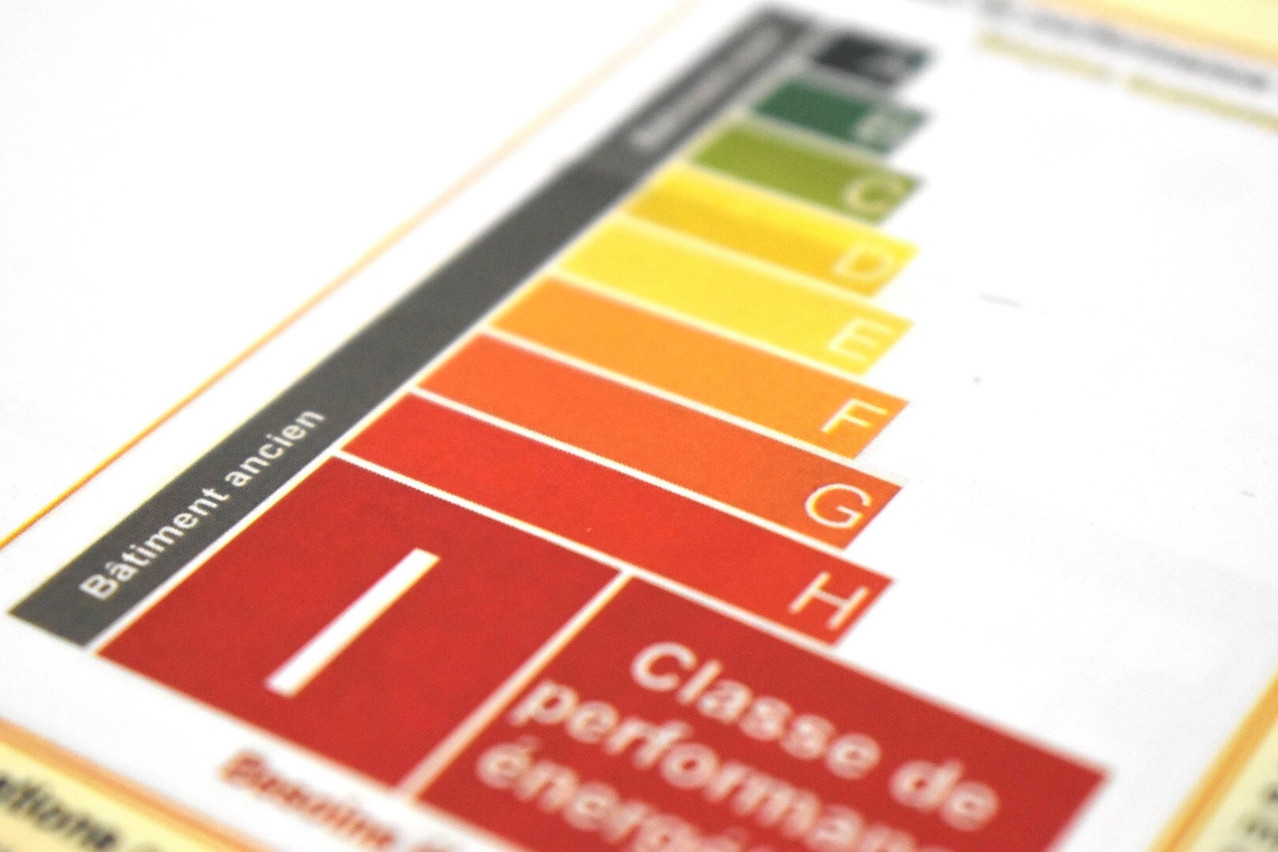

As most people in Luxembourg are aware, buildings in this country are subject to energy ratings that go from a dark green “A” to an alarm-ringing red “I”. Handed out on an energy performance certificate (EPC), the rating is based on the building’s energy and heat requirements as well as its CO2 emissions.

“Today, most people feel like they have to comply with the regulations, that they need the certificate. That’s it.” So says Sylvain Kubicki of the Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology (List). But the future holds something else, according to the researcher: “The use of these certificates in the next months and years might have much more impact, in the sense that they can affect the value of a property.”

“More than today,” he clarifies.

This perspective comes in a context of rising energy costs and, more generally, attempts at local and EU levels to improve and standardise the energy rating system. The wider context, of course, is the climate crisis and the EU’s Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, under which the building sector is meant to be climate-neutral by 2050.

Kubicki, principal investigator of a five-person research team at the List working on an updated EPC, spoke to Delano about the weak points of the current certificate and how it can be strengthened.

The energy rating system for buildings is being overhauled, with an aim for more reliability and comparability. Photo: Maison Moderne

We need more information!

You’ve just bought a house built in 1950s. Bits of it have been renovated over the years, but the radiators look old and, frankly, too weak to keep out Luxembourg’s long winters. Meanwhile, the master bedroom is under the roof and you can already see yourself frying in the summer heat come August.

What can you do about it?

This is the crux of the problem: people need not only more accurate information about a building’s energy performance, but also concrete recommendations on how to tackle the problem--such as which renovations to do and in what order.

The answer to these questions lies in an updated energy performance certificate. According to Kubicki, the current EPC is not precise enough and its calculations aren’t reliable. Plus, comparison between certificates is hard, depending on when they were carried out. And between buildings in different EU member states it’s even harder: “Even between Belgium and Luxembourg,” he says.

Cost will be another issue, of course, which is why sustainable finance officers in the banking sector the importance of transition finance.

EPC Recast

In order to address some of these problems and revitalise the energy rating system, the European Commission has funded a project called EPC Recast, which has 11 partners around Europe. Luxembourg’s iteration, headed up by Kubicki, is housed at the List. The new EPC, explains the researcher, will ideally enable users--including ordinary users like homeowners--to understand how they can save energy, including which specific renovations or other measures they can take.

The project has several aspects, Kubicki explains. For starters, it seeks to make energy measurements more accurate, which is a must, given the increasing dynamism of the data (e.g. constant feedback from smart sensors). Another aspect is a “renovation roadmap” that can help people plan renovations more strategically, currently a challenge because projects might require several years to take full effect and because each construction faces unique issues depending on its age, building materials, design, etc. And a final part of the project is to go beyond energy efficiency and also measure CO2 emissions, water consumption, resource use and other impacts.

Most immediately, the List project hopes to establish a set of indicators to recommend to the European Commission and the Luxembourg government for future regulatory updates. “This is a top-down outcome,” says Kubicki. “But the bottom-up is really to work together with our pilot dwellings.” By this he means a house in Olm where the List is testing its research in search of practical improvements. In parallel, EPC Recast has test houses in five other EU countries, looking at a range of building types and energy retrofit strategies.

Smart buildings

Part of what makes designing a new EPC a complex job is the influx of new technologies, as buildings increasingly have smart systems like automated window blinds, ventilation and lighting. Alternative construction materials to concrete and steel , such as wood or wood composites, with changes in insulation coming alongside. “All of that has an interesting impact on the energy efficiency of buildings,” Kubicki remarks.

A new scheme from the European Commission, the Smart Readiness Indicator (SRI), takes these changes into account directly. Currently optional for member states, the SRI measures a building’s capabilities to sense, interpret, communicate and respond to changing internal conditions, whether related to systems being used, the outside environment, the energy grid or actions by the occupants.

Finally, new technology could also offer improvements when it comes to assessing a building in order to assign it an energy class. Kubicki mentions a new app for assessors called ARtoBuild: it scans an internal space and delivers a 3D model, on top of which you can put the necessary details to produce the EPC.