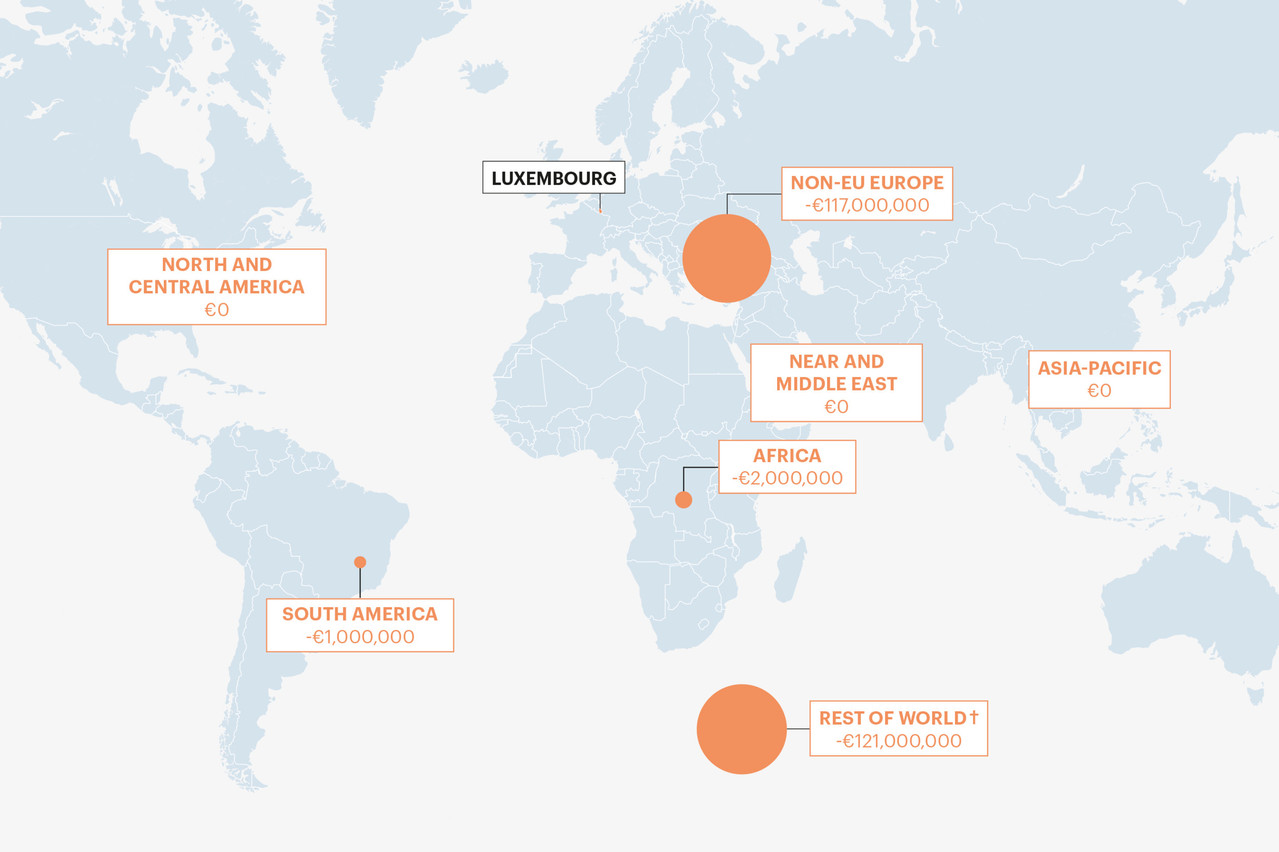

Net remittances

This map summarises the net balance of personal transfers (incoming minus outgoing transfers) between Luxembourg residents and non-EU27 households in 2020. “The majority of personal transfers consist of flows of money sent by migrants to their country of origin,” explains Eurostat. Luxembourg residents predominately send cash to non-EU European jurisdictions.

† Includes certain enclaves, overseas territories and international organisations. Source: Eurostat. Graphic: Maison Moderne

Outward remittances

Operating in Luxembourg

My take: Sending money home

Despite the pandemic, migrants have continued to send money to their families. Global remittances to low- and middle-income countries grew 7.3% to $589bn in 2021, according to an estimate by the World Bank. It forecast growth of 2.6% in 2022.

Migrant remittances are a “critical lifeline” in helping households cover essentials like food, healthcare and school fees. That is probably why the global recession only knocked 1.7% off the flow of funds in 2020.

However, the cost of sending money home is high. Remitters shell out an average 6.4% to transfer $200, the World Bank said. That is more than twice the sustainable development goal of 3% by 2030. (Merchants in the rich world pay roughly 1%-2% for payment card transactions. Nearly all bank transfers on the EU’s Sepa system are free.)

Ideally, as technology improves and volumes expand further, costs will come down. Perhaps that is a tangible target for the payments sector in Luxembourg, home to a notable number of (white collar) migrants.

A version of this article originally appeared in Delano’s print edition