At the same time, panellists said the supply of constructible land within Luxembourg City was sufficient for the medium term, but more needs to be done to promote affordable housing.

The comments came during the “Luxembourg, ville tentaculaire?” (Luxembourg, a sprawling city?) roundtable organised by the Paperjam Club. The event, held Tuesday evening, marked the release of the Winter 2016 edition of Archiduc magazine. (Both are part of the same company as Delano.)

Among the topics tackled, panellists discussed upward sprawl, or the question of population density and building height limits.

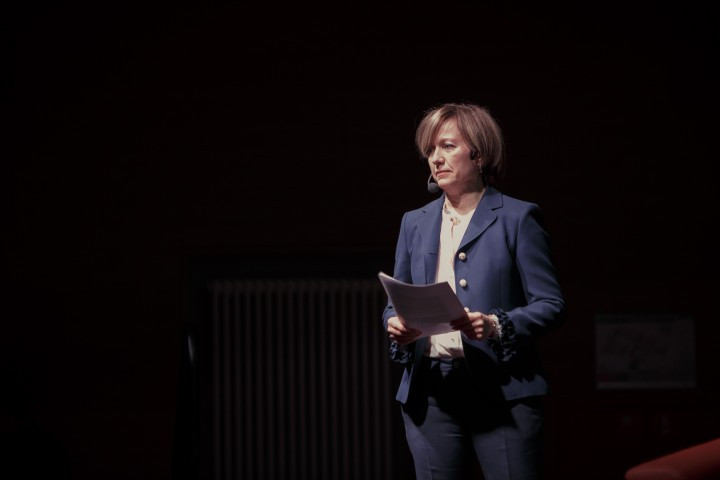

The conference was also a chance for Lydie Polfer, the DP mayor of Luxembourg City, to defend the capital’s draft PAG (Plan d’aménagement general, or master development plan). The PAG was published over the summer and aims to show how the city will handle an estimated doubling in population in the next two decades. At one point, Polfer claimed that critics of the PAG “hadn’t really read it”.

Urban development plan

According to the mayor, one problem with creating a coherent development plan is that the city cannot use eminent domain rules for private projects (although it can force landowners to sell for public initiatives). “Sometimes we have problems” negotiating a purchase from landowners, explained Polfer. That is what happened to long-stalled plans to include 49 boulevard Royal in Hamilius redevelopment programme.

More broadly, a big historical error, said François Bausch, the Green infrastructure and sustainable development minister, was letting certain areas become too jobs- or too residential- focused. Kirchberg, to cite one such case, is not a great area to live in. “No one wants to take a stroll along avenue [J.F.] Kennedy”, he argued. In other words, there needs to be a better mix of employment and housing in each of the city’s neighbourhoods to boost liveability.

Christine Muller, a partner at Dewey Muller Architectes et Urbanistes, thought cars have had too prominent a place in urban planning. She called for the end of strict formulas fixing the number of parking spots needed to develop a given plot of land. The rest of the structure is simply designed around that quota, she said. (Polfer replied that the number of parking spaces required in the new PAG had already been reduced.)

Is there still enough space?

A frequent suggestion is that Luxembourg City simply is not big enough to handle predicted growth. But Polfer stated in her introductory comments that around 25% of the city’s urban surface was not yet built up, leaving plenty of room for development while preserving green spaces and recreational facilitates.

Responding to a moderator’s question later on, Polfer pointed as a prime example to the proposed plan to move Josy Barthel stadium, the central fire station and the city’s recycling centre from Belair to Kockelscheuer, on the capital’s southern border. Polfer said “knock on wood” the deal would go through, which would then open up a huge swath of land in the heart of the city for housing construction.

Indeed, the city should not expand its borders, Bausch stressed, as there is plenty of potential in other areas, including Gare, Gasperich, Hollerich and Rollingergrund.

At the same time, authorities should keep in mind the success of the Grand Duchy’s financial centre, argued Vincent Bechet, president of the real estate trade group Luxreal and managing director of Inowai Group. Since work on the new PAG began, in 2014, six Chinese banks announced they would set up EU headquarters in Luxembourg, he commented.

Later, Bechet said that investment funds want their address to be in Luxembourg City itself, and not in a suburb, for reasons of prestige. So like it or not, “very soon the question will come up” of needing to expand the city’s territory.

Affordable housing

The economy is doing well and salaries are high in Luxembourg, conceded Markus Hesse, a professor of urban studies at the University of Luxembourg, but what about people seeking homes? Housing prices remain high too, he observed.

Muller cited the example of Vienna, whose city administration facilitates big projects to ensure a steady supply of affordable housing enters the marketplace. “Access to home ownership is my biggest worry” about Luxembourg City’s future, she said. More could be done, in her view, to promote forms of cooperative ownership. Instead of planning a single family house, three homes could be built on the same plot, for instance.

Bausch noted that, prior to the DP-LSAP-Green coalition government which took office in 2013, state-owned land destined for housing development was auctioned off at market prices. His ministry has started experimenting with selling land at 30%-40% below market rates, which he hopes will moderate the cost of housing somewhat. Bausch said: “even if prices remain high, perhaps they can be stabilised” instead of continually rising.